Living Inside Taste

What Grayson Perry Got Right About Class, Aesthetics, and Belonging

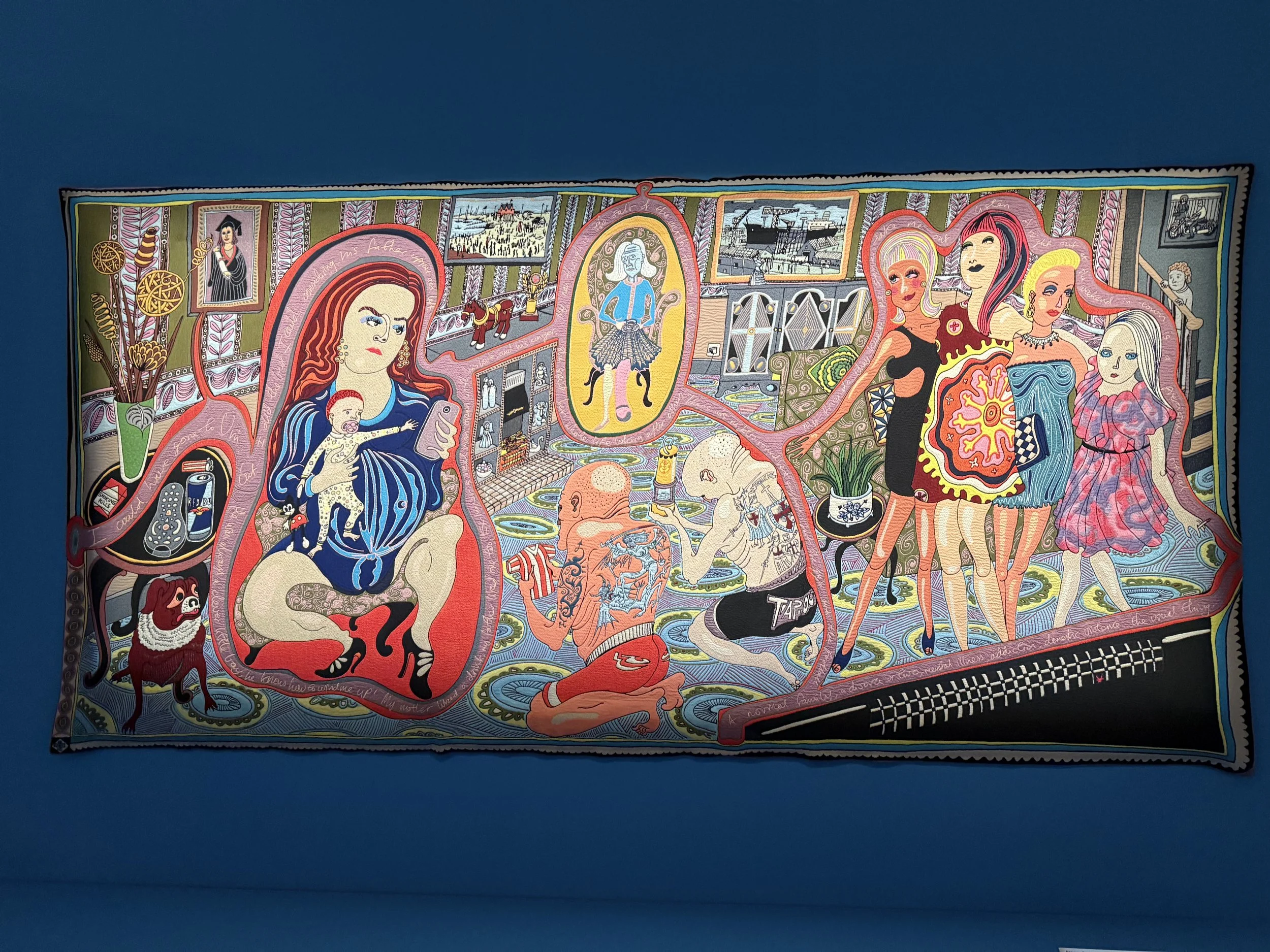

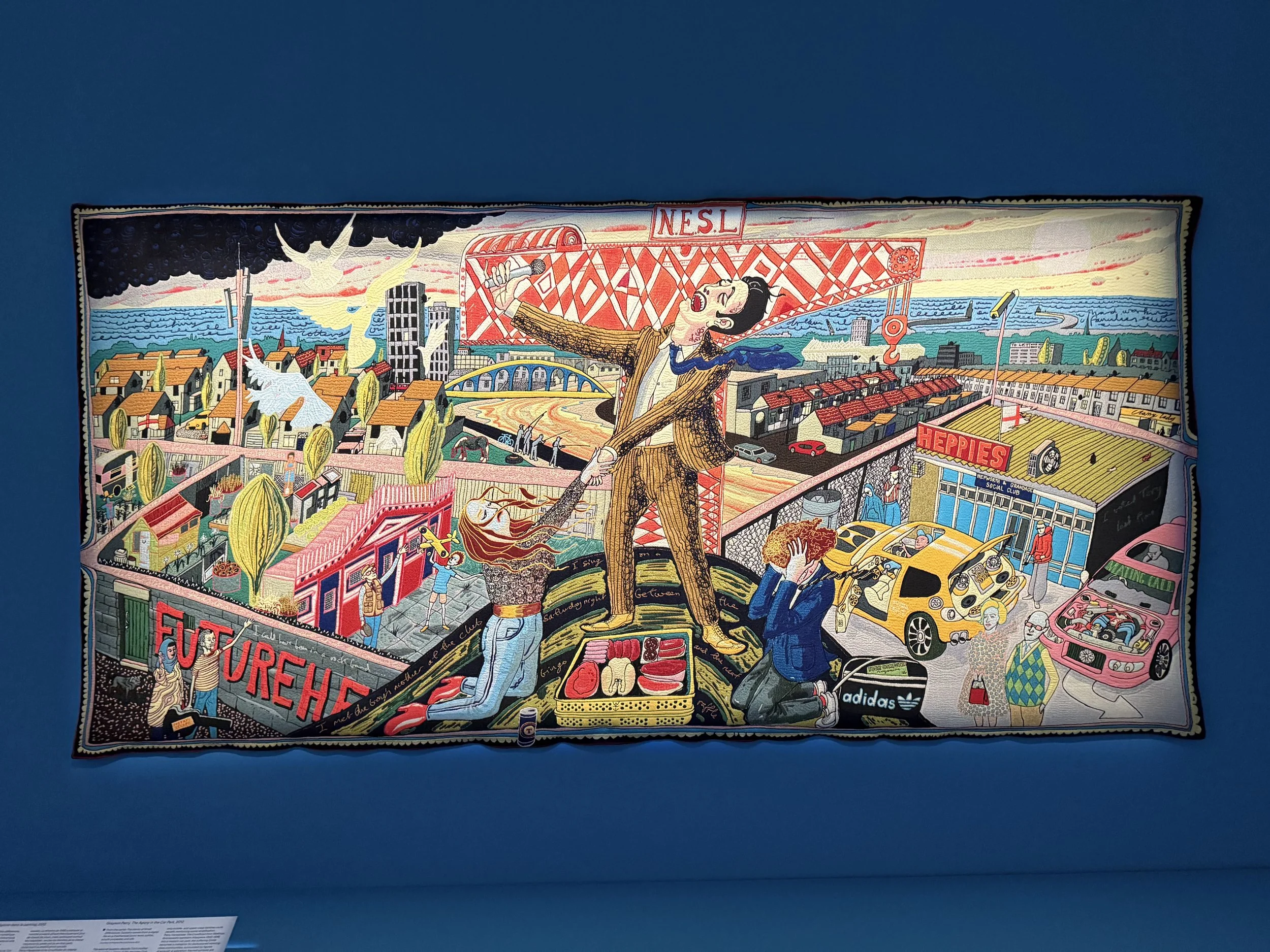

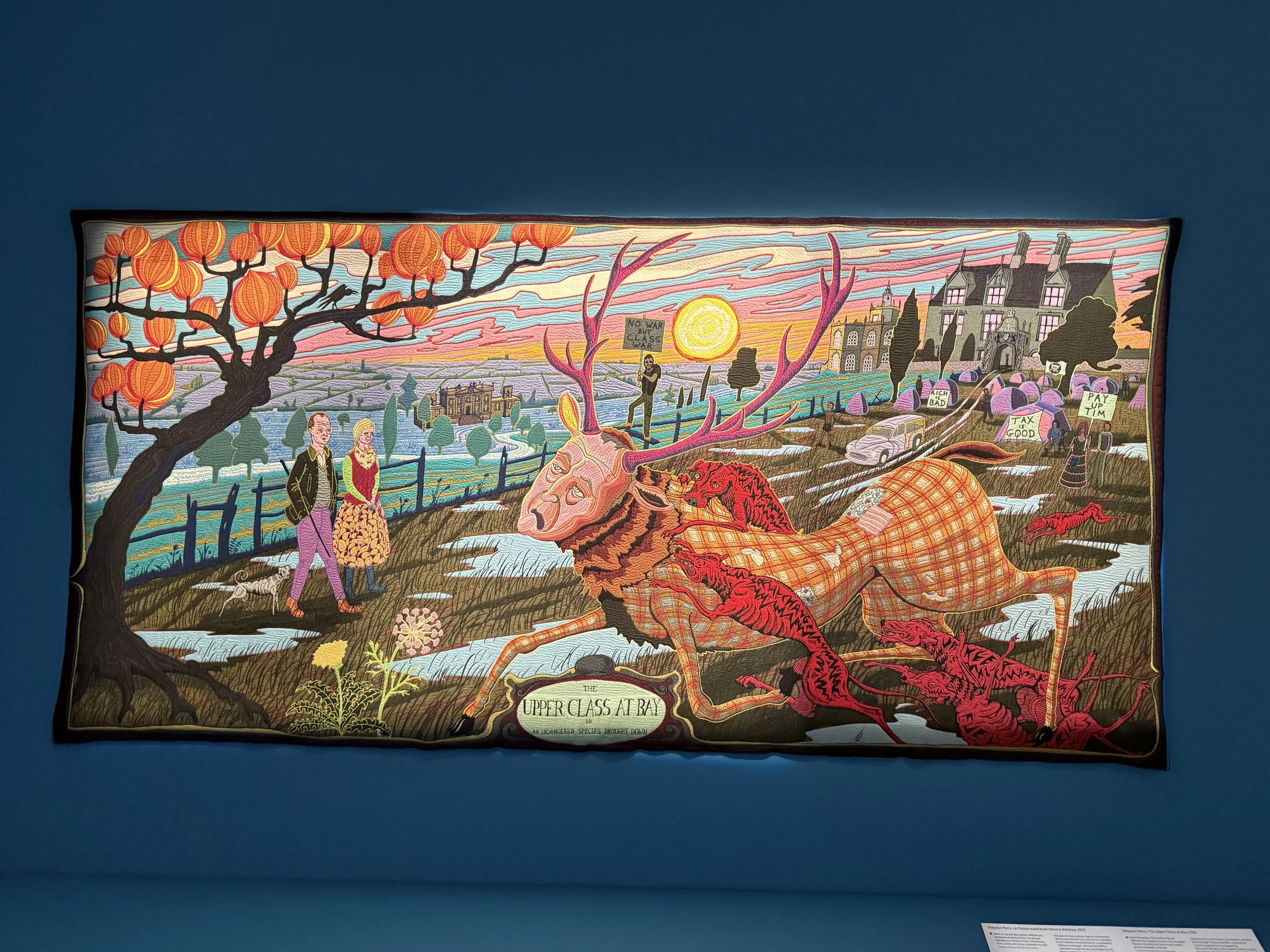

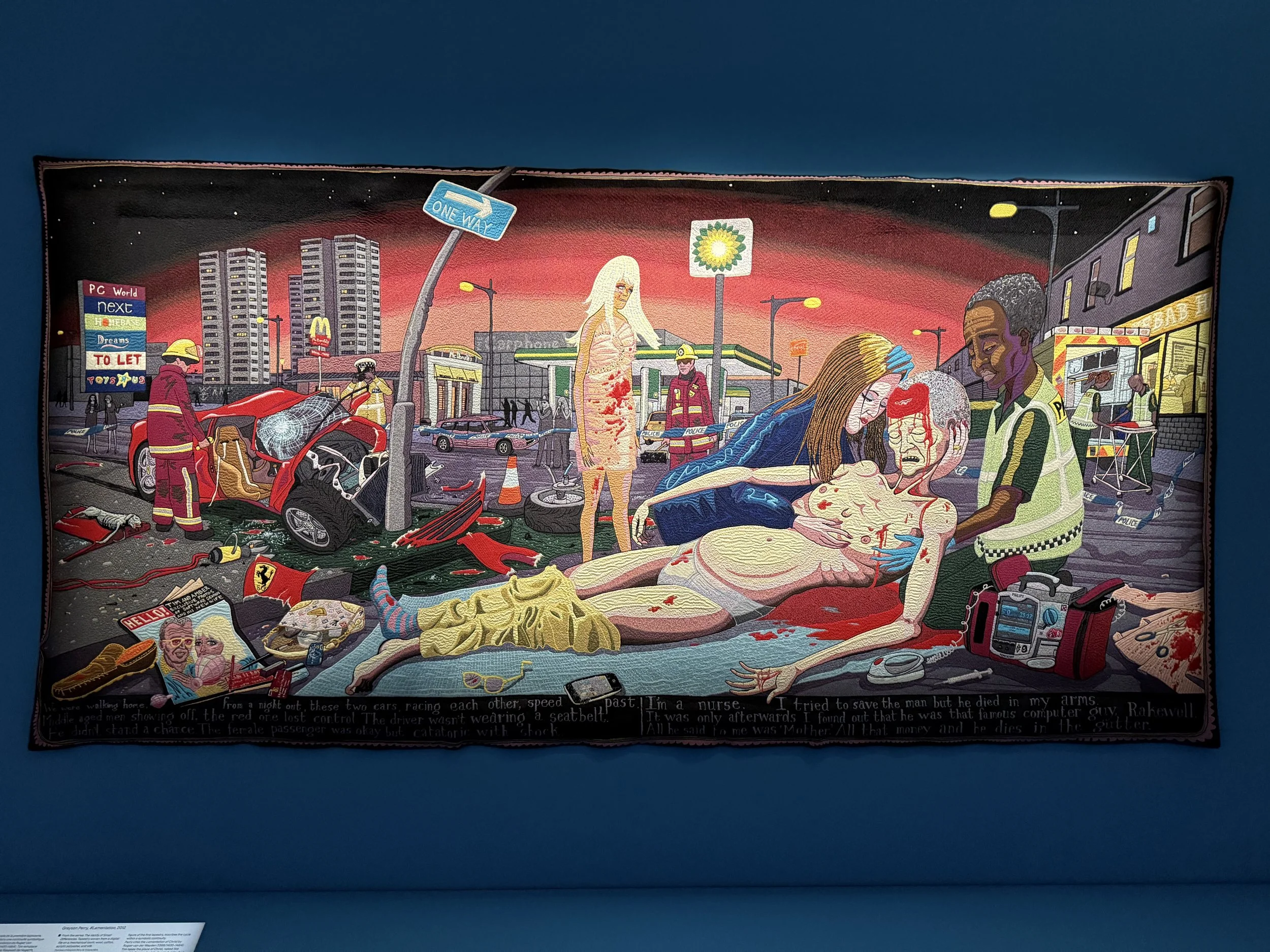

I just visited the exhibition in Lausanne connected to Grayson Perry’s 2012 documentary series All in the Best Possible Taste. At the center of it are the six monumental tapestries titled The Vanity of Small Differences, works inspired by William Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress. Together they follow the fictional life of Tim Rakewell, charting his movement through social classes, and how taste, aspiration, and identity quietly shape and betray him along the way.

Seeing these tapestries in person is overwhelming in the best way. They are dense, opinionated and deeply observant. Perry doesn’t mock class from a distance, he documents it from the inside. Every object, brand, and decorative choice carries meaning. Nothing is accidental. Taste becomes a language you learn long before you realize you are fluent in it.

What struck me most is how closely this mirrors my own experience.

For a long stretch of my life, my phone was brilliant not because of the camera, but because it let me live. I didn’t just observe different social segments, I stayed with them. I shared meals, routines, living rooms, and long conversations with people across working class, middle class, and upper class environments. I wasn’t studying them, I was embedded. You start to feel the differences before you can name them. The pace of speech, the way money is talked about or avoided, what is considered practical versus indulgent, what is displayed and what is hidden.

Grayson Perry says that nothing influences aesthetic taste more than the social class we grow up in. Taste is not about refinement or intelligence. It is about belonging. It is about signaling safety to your tribe. The tragedy Perry captures, and Hogarth before him, is that class mobility often demands abandoning one visual language before fully mastering another. You end up fluent in neither.

As a designer, this matters deeply.

Good design is not neutral. It carries values and it reveals who it was made for and who it quietly excludes. Walking through this exhibition reminded me that design is never just about beauty. A chair, a font, a logo, or a kitchen backsplash can tell you exactly where someone believes they belong, or desperately wants to.

Perry’s tapestries succeed because they refuse to flatten people into stereotypes. They show how taste is inherited, performed, and sometimes weaponized. They also show how small the differences really are.

And as someone who builds brands, tells stories, and moves between worlds, that might be the most valuable reminder of all.